Post Type: Preliminary deep…ish dive

Epistemic Certainty: Still learning

This post started as curiosity about coffee history after hearing a podcast and turned into this monster. It’s part historical research, part personal obsession, and part me just trying to figure out how the hell we got from Ethiopian goats to Starbucks. You’ve been warned. This post was co-written with Claude. I did the research, voice dictated my thoughts, and Claude organized those voice notes into a coherent post.

What’s Your Definition of Heaven?

A strong cup of filter coffee. A place to sit—could be a park, the terrace of your house, or even a curve by the road. Add a good book or a few long-form articles. If that isn’t heaven, I don’t know what is.

I’ve long been a coffee addict. It’s my beverage of choice, my cigarette, my addiction, my wife. Life feels incomplete without a strong cup of filtered coffee in the morning. To this day, nothing generates the kick that coffee does. Not all the powdery substances, not all the synthetic drugs in the world can give me the high that coffee provides. (And trust me, I’ve tried caffeine pills—they’re garbage compared to actual coffee.)

Why am I talking about coffee? During one of my doomscrolling sessions on PocketCasts, I came across a BBC Radio episode titled “A History of Coffee” from the podcast You’re Dead to Me. The guest was Professor Jonathan Morris, who’s written a book called Coffee: A Global History—and you know what my next book purchase will be. (Already in my Amazon cart because apparently I have no self-control when it comes to books.)

I heard the episode and was absolutely hooked. Being a coffee lover who wants to go on a coffee pilgrimage around the world at some point (yes, I’m that guy), I couldn’t wait to learn more. So I asked Claude to give me a broader history of coffee, and I’ve got to say—these AI tools, when used well, are phenomenal learning companions. Way better than pretending to be smart by just nodding along to podcasts.

This post is a placeholder for me to explore coffee’s history in much greater depth later. It’s a shitty first draft of a shitty first draft. Consider it a potted version—a starting point for a future deep dive into the fascinating world of coffee. It’s basically me trying to organize my thoughts after going down the coffee rabbit hole for the first time.

The Ethiopian Origins: From Myth to Reality

The popular myth goes like this: On a beautiful day in 9th-century Ethiopia, with the sun shining bright and a gentle breeze sweeping the lush grasslands, a goat herder named Kaldi noticed something peculiar. His goats became energetic after eating red berries from a bush, acting like they were on drugs. Curious, Kaldi investigated the bush and discovered coffee.

This story is apocryphal—made up. But it’s a nice story, so I’m keeping it.

What we do know is that Ethiopians were the first people to consume coffee, based on current archaeological evidence. Coffee has special significance in Ethiopian culture that persists today. Ethiopian monks initially ate the berries whole and made fermented beverages from coffee beans. (Can you imagine just eating coffee beans? That sounds intense.) Archaeological evidence suggests Ethiopians were consuming coffee in various forms centuries before it spread beyond Ethiopian borders.

The Oromo people in Ethiopia have traditional coffee ceremonies going back generations, treating the plant as sacred and central to their culture. The Ethiopian coffee ceremony, one of the world’s oldest coffee rituals, is exclusively performed by women. It’s an elaborate process involving roasting beans over an open fire, grinding them by hand, and brewing in a clay pot called a jebena.

Here’s what’s fascinating: Ethiopian women didn’t just perform ceremonies—they controlled the entire knowledge system around coffee. They knew when to pick cherries, how to process them, how to store them. This knowledge was passed down through generations, making women integral to coffee’s cultivation and trade. Keep this in mind, because it’s a pattern that would repeat (with some unfortunate twists) as coffee spread globally.

The Islamic World: From Sacred Substance to Political Space

Coffee cultivation and trade became systematized as it spread to Yemen in the 15th century, particularly around the port city of Mocha. Sufi mystics embraced coffee as a stimulant to keep them alert during nighttime prayers and religious ceremonies, finding that its effects helped them achieve heightened spiritual awareness.

Coffee quickly spread throughout the Ottoman Empire, where it developed profound religious and cultural significance. According to Ethiopian tradition, coffee was a divine gift to humanity, discovered when the archangel Gabriel appeared to a monk and revealed the stimulating properties of the plant. Islamic scholars like Al-Jaziri wrote extensively about coffee’s spiritual benefits, arguing it was a gift from Allah.

But coffee also sparked centuries of religious debate. Orthodox Islamic scholars worried about this “dangerous innovation” whose consumption wasn’t explicitly authorized by Islamic law. Throughout history, there were numerous legal rulings and fatwas against coffee consumption. In Mecca, coffee was banned multiple times, and coffee houses were periodically prohibited—though these bans were often quickly overturned.

Here’s what surprised me: the first coffeehouses didn’t emerge in England, as most people assume, but in the Ottoman Empire. These coffee houses, called qahveh or kahveh, were important social institutions throughout the Islamic world. In Constantinople, Damascus, and Cairo, they were known as “schools of the wise”—centers of intellectual discourse, political debate, and social gatherings.

Coffee houses were essentially the first social networks. Before Facebook and Twitter, this is where people went to network, share information, and form alliances. But like most gathering places throughout history, they also became venues for subversive and revolutionary dialogue, leading to periodic attempts to shut them down.

The Arabs maintained a tight grip on the coffee trade, holding an almost complete monopoly. They prohibited the export of seeds, maintained strict control over cultivation, and boiled and roasted beans before exporting them to prevent germination and safeguard their secrets.

European Expansion: From Satan’s Drink to Revolutionary Catalyst

By the early 17th century, Venetian merchants had brought coffee to Europe. The reception was mixed in Christendom—many dubbed it “Satan’s drink” because of its association with Islamic culture. Christian theologians worried it was a Muslim plot to corrupt Christian souls and weaken Christian society. An apocryphal story claims that Pope Clement VIII blessed coffee, offering it benediction and declaring it acceptable for Christians to consume, though this appears to be popular legend.

The first European coffee houses opened in Venice, followed by London in 1652, then Paris and Vienna. London’s coffeehouses became known as “Penny Universities”—for the price of a coffee (one penny), people could engage in intellectual conversations and access newspapers and pamphlets.

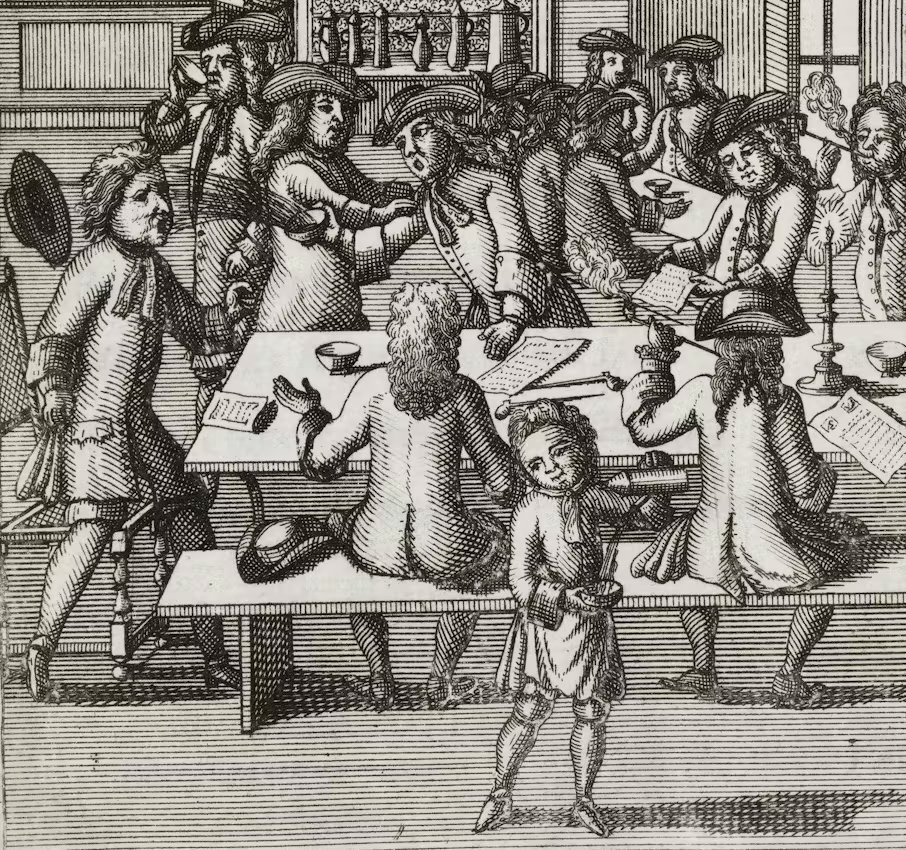

A disagreement about the Cartesian Dream Argument (or similar) turns sour, note the man throwing coffee in his opponent’s face. Detail from the frontispiece of Ned Ward’s satirical poem Vulgus Brittanicus (1710) and probably more of a flight of fancy than a faithful depiction of coffeehouse practices — Source.

Coffeehouses played crucial roles in the development of banking, insurance, and stock trading. They became places for commercial dealings, and Lloyd’s of London Insurance Market famously began in Edward Lloyd’s Coffee House. New York coffeehouses also served as unofficial stock exchanges, where merchants organized boycotts and political opposition was formulated.

But coffee houses also became sites of political resistance. King Charles II of England attempted to ban them in 1675, calling them “seminaries of sedition.” In France, coffeehouses played a key role in the French Revolution. Enlightenment philosophers like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot met in coffee houses, and revolutionary leader Camille Desmoulins delivered some of his most famous speeches in Parisian cafés. The call to arms that started the French Revolution was supposedly given at Café de Foy in 1789, when Desmoulins jumped onto a table and urged the crowd to take up arms.

The American Revolution: Coffee as Patriotic Resistance

The American Revolution provides one of the most dramatic examples of coffee as a revolutionary instrument. After the Boston Tea Party in 1773, boycotting British tea led to the search for a new drink. Since coffee wasn’t controlled by the British, it became the patriotic drink of choice for American colonists.

Coffee consumption became not just a shift away from tea but a political act—an act of resistance and declaration of independence from British influence. American revolutionaries promoted coffee consumption as a patriotic duty, and coffee houses served as crucial organizing spaces for resistance against the British.

The Forgotten Half: Women in Coffee’s Hidden History

Coffee’s history is often told through a male perspective—male merchants, plantation owners, coffee house patrons. But women have played key roles in every aspect of coffee’s journey, often in ways that reveal the deep gender inequalities that coffee’s spread both reflected and reinforced.

As coffee spread through the Islamic world, gender dynamics became complex. Ottoman coffee houses were almost exclusively male spaces, cutting women off from the intellectual and political discourse happening there. Women were prohibited from entering coffeehouses, denying them access to information and networking opportunities.

But women found workarounds. In Ottoman households, women created their own coffee culture in harem quarters, developing elaborate coffee service rituals and becoming connoisseurs of different brewing methods. The quality of a woman’s coffee-making skills supposedly became a symbol of her marriageability and social status.

In London, women’s exclusion from coffeehouses led to significant resistance. The famous “Women’s Petition Against Coffee” (1674) was a satirical pamphlet arguing that men were spending so much time in coffee houses that they were neglecting their wives and families. It blamed coffee for making men weak and argued that “the Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE” had made their husbands “as Impotent as Age.”

Despite exclusion from coffeehouses, women found ways to participate in coffee culture. They could be owners of coffeehouses even if not patrons, and there were several examples of women-owned establishments in London and other European cities.

Breaking the Monopoly: Dutch Innovation and the Dawn of Exploitation

The Dutch broke the Arab monopoly on coffee trade in the 1690s through a combination of espionage and colonization. They obtained coffee plants and established plantations in Java and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), transforming coffee from a beverage limited to the Arab world into a global commodity.

The Dutch East India Company was vertically integrated, controlling every aspect from cultivation to final sale in European markets. They developed standardized growing practices and pioneered new financial instruments, including joint stock ownership and commodity futures, to manage the risks of large-scale coffee production.

But this expansion came with a dark side. In Java, the Dutch implemented a system where indigenous farmers had to dedicate portions of their land and labor to export crops like coffee. This led to widespread famine and suffering among local populations, with thousands dying from overwork and malnutrition.

The Caribbean: Coffee’s Most Shameful Chapter

Coffee expanded to the Caribbean in the early 18th century, representing perhaps the most shameful chapter in coffee’s global spread. The French established coffee plantations in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), run entirely on enslaved African labor under reportedly the most brutal conditions in the history of slavery.

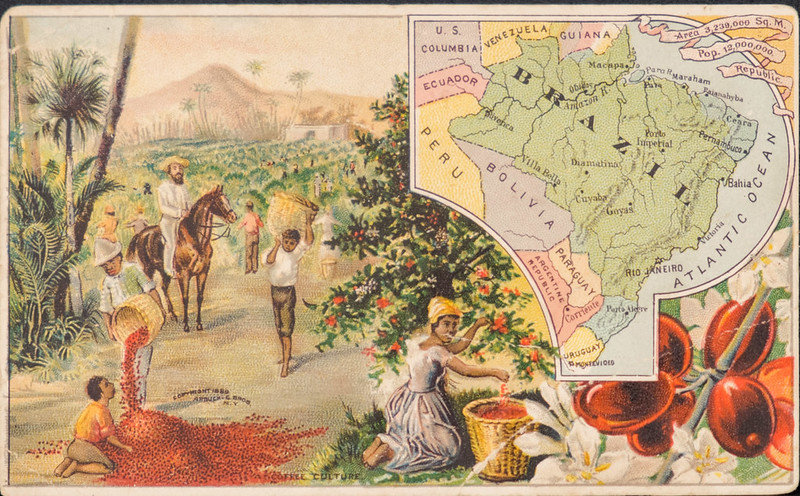

Slaves working on a coffee plantation

Here’s a shocking fact that haunts me: the average life expectancy for a newly arrived slave was less than seven years. As someone who enjoys coffee, I hadn’t realized there was such a dark side to this humble bean, and it’s still causing conflicting thoughts in my head.

The profits from slave-run coffee plantations were enormous for colonial superpowers, creating immense wealth for French plantation owners and merchants. This was blood money directly extracted from the suffering of enslaved people who were forced to relocate to Caribbean plantations.

Enslaved women faced particular horrors—they were forced to work in brutal conditions while also being compelled to reproduce under exploitative conditions, giving birth to the next generation of slaves. They faced sexual violence from plantation owners and overseers, and mortality rates were extremely high from exhaustion, disease, and childbirth complications.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), led entirely by enslaved people fighting for their freedom, effectively ended the Caribbean’s dominance in coffee production. As Caribbean production declined, Brazil became the biggest coffee exporter.

Brazil: An Even Larger Scale of Exploitation

Brazil’s coffee production expanded rapidly from the 1800s onward, but here’s another shocking fact: Brazil’s coffee industry was built on an even larger scale of slavery compared to the Caribbean. By 1850, Brazil was the largest coffee exporter, and even until 1888, the Brazilian coffee industry enslaved millions of Africans.

.jpg)

Coffee; from plantation to cup

The profits from slave-produced coffee directly funded the building of cities like Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, creating a powerful class of coffee barons who dominated Brazilian politics for generations. The legacy of this system is still visible in Brazil’s society today—racial and economic inequities can be traced back to the plantation era.

Representation of coffee cultivation in Brazil, 1889

Coffee as Medicine: From Traditional Remedies to Modern Science

In the Ethiopian Highlands, traditional medicine practitioners called hakims used coffee in various forms for millennia. Coffee leaves were brewed as tea for headaches and stomach problems, berries were consumed whole or as fermented beverages for digestive issues, and coffee bean oil was used to treat skin conditions and wounds.

Islamic physicians developed sophisticated understanding of coffee’s medicinal properties, incorporating it into their medical practices based on the Greek doctrine of humors. They prescribed coffee to balance the four body fluids (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile). Al-Jaziri wrote the first extensive work on coffee’s medicinal properties in the 16th century, titled Umdat al-Safwa fi Hilal al-Qahwa (The Reliable Source on the Permissibility of Coffee).

The scientific revolution came in 1819 when German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge isolated caffeine after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gave him coffee beans to investigate. Runge himself recounted the story:

“After Goethe had expressed to me his greatest satisfaction regarding the account of the man whom I’d rescued [from serving in Napoleon’s army] by apparent ‘black star’ [i.e., amaurosis, blindness] as well as the other, he handed me a carton of coffee beans, which a Greek had sent him as a delicacy. ‘You can also use these in your investigations,’ said Goethe. He was right; for soon thereafter I discovered therein caffeine, which became so famous on account of its high nitrogen content.”

This identification of caffeine as coffee’s active ingredient revolutionized medical understanding, allowing physicians to explain coffee’s stimulative effects for the first time.

By the early 20th century, people worried coffee would cause cardiac diseases, nervous system disorders, and various other health problems. But by the 1980s, more sophisticated scientific understanding emerged, showing that moderate coffee consumption was actually beneficial for heart health, diabetes prevention, and liver health, and provided protection against neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

The Economic Revolution: From Currency to Global Commodity

In the Ethiopian Highlands, coffee beans served as a form of local currency before standardized currency was introduced. The beans were portable, durable, divisible, and had intrinsic value, making them ideal for trade.

Yemen’s control of coffee from the 15th to 17th centuries created a near-monopoly that made the country almost entirely reliant on coffee exports. The port city of Mocha became the center of coffee trade, later giving its name to the famous coffee variety. The Ottoman Empire collected significant taxes on coffee trade, and many coffee merchants were among the wealthiest in the Islamic world.

Coffee profits played a key role in European expansion and industrialization. Coffee wealth funded the construction of Amsterdam’s famous canal houses and contributed to the Netherlands’ Golden Age. The New York Coffee Exchange was established in 1882 as one of the first formal commodity futures markets, pioneering financial instruments later applied to other commodities.

The Persistent Inequalities: Women in Modern Coffee

The gender inequalities established in coffee’s early history persist today. Women’s labor makes up a significant percentage of agricultural workers in coffee-producing regions: 20% in Latin America, 30-60% in Asia, and 50-75% in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Colombia, women are responsible for 75% of fieldwork and 70% of the drying and sorting of harvested cherries.

Despite this substantial contribution, women own a much smaller percentage of coffee farms and receive significantly less income than men. The historical inequities have persisted into the modern day, with women not only working on farms but also managing households—often working more than men while having less economic power. Organizations like the International Women’s Coffee Alliance are working to address these ongoing inequalities.

Coffee in the Modern World: From Industrial Commodity to Climate Crisis

By the 19th and 20th centuries, coffee had evolved from an agricultural product to an industrial commodity. The invention of the espresso machine in Italy (1884) and instant coffee (1901) made coffee more accessible to working-class people in rapidly industrializing Western countries. (Though I’m not sure instant coffee counts as real coffee—fight me.)

Large corporations developed industrial roasting technologies, packaging innovations like vacuum packaging, and mass-market brands. Companies like Folgers and Maxwell House created household names, and the industry became increasingly concentrated in the hands of multinational corporations like Nestlé, JAB Holdings, and Starbucks.

Today, coffee faces new challenges that would make all those historical coffee traders weep. Climate change is basically trying to kill coffee. Changing weather patterns are making coffee-growing regions unsuitable for cultivation, higher temperatures are screwing with yields and quality, and increased pests and diseases are making farmers’ lives miserable.

It’s ironic, isn’t it? All those centuries of exploiting people and places to make coffee profitable, and now the climate consequences of that exploitation are coming back to threaten the whole system. The places that were colonized for coffee are now the ones most vulnerable to climate change. History has a dark sense of humor.

Conclusion: What I Learned About Coffee (And Everything Else)

So here’s what I’ve figured out after going way too deep into coffee history: this whole thing is basically the story of human civilization in a cup.

From Ethiopian goats getting hyper on berries to the morning ritual that billions depend on today, coffee has been at the center of almost everything that matters—revolutions, economics, gender dynamics, colonialism, science, religion, climate change. It’s been a catalyst for political movements, an engine for economic exploitation, a medicine, a currency, and a symbol of resistance.

The more I learned, the more I realized how interconnected everything is. Ethiopian women’s traditional knowledge shaped global trade. Ottoman coffee houses influenced London’s political discourse. Caribbean brutality funded European prosperity. A German chemist’s discovery with coffee beans revolutionized medicine. The Haitian Revolution reshaped global markets. It’s all connected in ways that would make your head spin.

But here’s what really gets me: coffee’s journey reveals patterns that keep repeating throughout human history. The same dynamics of power, exploitation, resistance, and adaptation show up everywhere. We create amazing things, we exploit people to make them profitable, people resist and fight back, and somehow we muddle through to create something new. Rinse and repeat.

And now, as I sit here with my morning coffee, I’m reminded that this simple pleasure carries all of that complexity. The creativity and cruelty, the innovation and exploitation, the resistance and oppression. Every cup contains the full spectrum of human nature—our capacity for both incredible beauty and terrible ugliness.

I don’t know what that means for how I should drink my coffee. Should I feel guilty? Grateful? Aware? Probably all of the above. But I do know that understanding this history has made me see my daily ritual differently. It’s not just a drink—it’s a connection to thousands of years of human struggle and creativity.

Coffee’s story is our story. And that’s both beautiful and terrifying.

Learning with Claude (Or: How I Went Down Way Too Many Rabbit Holes)

So here’s the thing—after writing all this stuff about coffee, I realized I’d basically stumbled into a bunch of ideas that smarter people than me have been thinking about for decades. It’s like when you think you’ve had an original thought and then discover seventeen books have already been written about it. (Story of my life, honestly.)

But that’s actually the cool part. Coffee’s journey connects to so many big ideas about how humans organize themselves, exploit each other, resist power, and generally make a mess of things. Let me try to connect some dots, though I’m probably going to get half of this wrong.

The Economics Bit (Or: How Coffee Became Global)

Coffee’s evolution from Ethiopian currency to global commodity is basically the story of how capitalism works. There’s this economic historian named Fernand Braudel who had this concept called “world-systems”—essentially how local stuff becomes global. Coffee’s the perfect example. You start with Ethiopian women knowing when to pick berries, and you end up with commodity futures markets in New York.

The Dutch East India Company was basically the first multinational corporation, and they figured out how to control coffee from farm to cup. It’s what economist Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction”—they destroyed the Arab monopoly to create something new. Though in this case, “something new” involved a lot of colonialism and slavery, so maybe “creative” is the wrong word.

The New York Coffee Exchange that started in 1882 became one of the first modern commodity futures markets. Basically, people started betting on coffee prices before the coffee even existed. Which sounds insane but apparently that’s how modern finance works. (I still don’t fully understand futures markets, but they seem important.)

The Politics Bit (Or: How Coffee Houses Became Democracy)

This is where it gets really interesting. Coffee houses were basically the first social networks, but instead of arguing about politics online, people did it in person while drinking coffee. Philosopher Jürgen Habermas has this theory about the “public sphere”—spaces where regular people can debate public issues instead of just accepting what authorities tell them.

The Ottoman “schools of the wise” and London’s “Penny Universities” were early versions of this. People would gather, drink coffee, argue about politics, and sometimes start revolutions. The American Revolution’s embrace of coffee over tea is a perfect example of what Benedict Anderson called “imagined communities”—how shared practices create national identity.

Coffee houses also show what James C. Scott calls “hidden transcripts”—how people without power create spaces to criticize those with power. Which is probably why so many rulers tried to ban coffee houses. They correctly identified them as threats to their authority.

The Gender Bit (Or: How We Erase Women From History)

This part really bothered me. Coffee’s history is told almost entirely by men, about men, even though women were central to the whole thing. Historian Gerda Lerner pointed out how we systematically erase women from historical narratives, and coffee’s a perfect example.

Ethiopian women created and maintained the knowledge systems that made coffee possible. Ottoman women created parallel coffee cultures when they were banned from coffee houses. The 1674 Women’s Petition Against Coffee is hilarious but also shows how gender anxieties play out during periods of social change.

What’s depressing is how these patterns persist. Women still do most of the coffee work globally but own hardly any of the farms. Organizations like the International Women’s Coffee Alliance are trying to fix this, but it’s taking forever.

The Colonial Bit (Or: How Coffee Built on Suffering)

This is the darkest part. Coffee’s role in colonial exploitation shows what Edward Said called “Orientalism”—how Western powers justified domination through cultural narratives. The Caribbean and Brazilian plantation systems connect to Frantz Fanon’s analysis of colonial violence and its lasting effects.

The Haitian Revolution destroying coffee production shows how enslaved people’s resistance could reshape global markets. But it also shows how the profits from coffee slavery funded European cities and created wealth that still exists today.

The Science Bit (Or: How We Figured Out What Coffee Actually Does)

Coffee’s evolution from traditional medicine to modern science is fascinating. Different cultures had different “explanatory models” (as medical anthropologist Arthur Kleinman calls them) for how coffee worked. Islamic physicians used the Greek doctrine of humors, Ethiopian hakims had their own systems.

Then Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge isolated caffeine in 1819 and everything changed. Suddenly we could explain scientifically why coffee works instead of just saying “it’s from God” or “it balances your humors.” This was a big moment in pharmacology—the transition from traditional plant medicine to modern chemistry.

The Climate Bit (Or: How History Comes Back to Bite Us)

Coffee’s vulnerability to climate change connects to what Jared Diamond writes about—how environmental problems can destroy civilizations. The shift from diverse indigenous agriculture to coffee monocultures is a classic example of short-term thinking creating long-term problems.

Climate research on coffee shows how all those historical patterns of exploitation are coming back to threaten the whole system. The places that were colonized for coffee are now the ones most vulnerable to climate change.

What I’m Still Trying to Figure Out

I keep thinking about how coffee connects to bigger questions about power, culture, and human nature. Like, why do the same patterns of exploitation keep repeating? Why do revolutionary spaces (like coffee houses) eventually get co-opted? How do we balance appreciating coffee culture with acknowledging its dark history?

I don’t have answers to any of this. But that’s what makes it interesting, right? Every cup of coffee carries all of this history—the creativity and cruelty, the innovation and exploitation, the resistance and oppression. It’s like drinking civilization itself.

Some Places to Keep Learning:

-

Coffee Research Institute - Academic stuff on coffee’s social impact

-

Smithsonian’s Coffee Collection - Visual history materials

-

Atlantic Slave Trade Database - Depressing but important data

-

Ottoman History Podcast - Academic discussions of coffee house culture

-

Fair Trade Research - Modern efforts to fix historical problems

This whole section is basically me trying to make sense of how a simple drink connects to the biggest questions about human nature. I probably got half of it wrong, but that’s what makes it fun to think about. Every time I learn something new about coffee, it changes how I see everything else.